It often feels like we just can’t catch a break. Gen Z is facing tough challenges: mental health struggles, the pressures of social media, uncertainty about the future, unemployment, and economic insecurity. We also deal with climate anxiety, social inequality, and the feeling that our voices aren’t being heard. Education systems are slow to adapt to modern needs, while digital overload and loneliness make it harder to find real connections and balance. Yet, rather than focusing on these complex challenges directly, this article will explore a simpler question: Could something as straightforward as access to green spaces help improve young people’s quality of life, and if so, how? Can green spaces make a difference?

First and foremost, why is this topic relevant? Well, all residents of modern cities (not just youth) are feeling the effects of urbanization, overbuilding, and climate change. As cities grow and greener areas disappear, questions arise about how this affects our everyday lives. On the other hand, many studies show that spending more time in green spaces is linked to better mental health and well-being among young people. It can help reduce stress, improve mood, and increase life satisfaction. Young people who have access to parks, trees, and nature often report fewer signs of depression and feel happier overall. But let’s break this down step by step…

Nature as the new reset button

We are surrounded by images, spending a lot of time online. On an everyday basis, this, of course, affects our mental health. Spending time in nature, however, can help reduce anxiety and depression in adolescents. A study of over 10,000 Iranian teens found that visiting green spaces (parks, forests, and gardens) was linked to higher self-satisfaction and better social connections. Teens with more social contact in these spaces reported feeling happier, and older adolescents showed the strongest benefits. Access to green spaces can be an easy and effective way to support young people’s mental well-being (Dadvand et all, 2019). In addition, green space appears most consistently linked to improvements in mood and stress reduction, though benefits have also been observed for depression, emotional well-being, mental health, and behavior (Zhang et all, 2020).

Beyond their impact on health, green spaces also play an important social role. They serve as places for interaction, connection, and community building. The design and quality of neighborhoods influence how adolescents socialize, while in more deprived areas, limited and unsafe public spaces can restrict opportunities for gathering and play. Greening interventions (such as restoring vacant lots or improving parks) can create environments that encourage social interaction and community connection. Adolescents with access to parks and recreational areas often report stronger social networks and a greater sense of belonging. These spaces encourage physical activity, which in turn promotes positive social behaviors and reduces feelings of loneliness. Building on these insights, the Greening Theory of Change thus highlights how these initiatives not only provide green space but also foster social networks, support mental well-being, and reduce health disparities among youth. Project VITAL in Baltimore applies this approach, studying how greening programs strengthen social ties while improving adolescent health outcomes (Kondo et all, 2024).

On top of that, green spaces are not only essential for relaxation, socializing, and mental health, but also serve as spaces for environmental learning and civic action. Environmental awareness – understanding ecological issues and their impacts – lays the foundation for civic responsibility, motivating individuals to take action for the common good. Research showed that people who are more aware of environmental problems are also more likely to engage in sustainable behaviors, community projects, and environmental activism (Mironesco, 2020). In simpler terms: When awareness grows, responsibility follows! Programs that combine education with hands-on activities, such as community gardening or service-learning, help young people see themselves as agents of change. Factors like social norms, sense of place, and trust in institutions can further strengthen this connection, leading to lasting pro-environmental habits.

For example, global youth movements like Fridays for Future show how awareness can turn into collective responsibility and action. These initiatives prove that when young people understand the urgency of environmental issues, they can transform concern into meaningful change, making green spaces and activism symbols of hope, unity, and sustainability. But…

Why don’t we care more?

All of this raises an important question: if green spaces are so vital to our health and well-being, why aren’t we doing more to protect them? Why don’t we care more? Firstly, it is important to highlight that when we talk about the need for more green spaces, we are not just talking about parks and trees, but also about a fairer society that allows everyone access to these areas. Research shows that inequality also affects the environment: societies with larger gaps between rich and poor tend to have lower environmental awareness, higher consumption, and less care for shared resources. That is why the issue of green spaces is not only an aesthetic one but also a social matter of equality, solidarity, and sustainability.

Many theorists agree that greater equality benefits the environment, as citizens of a more equal and fair society tend to be more helpful, conscious, and even happier. In today’s capitalist-driven social system, the gap between the rich and the poor continues to widen, and their daily practices and consumption patterns differ greatly. Some of the super-rich spend money on luxury rather than on essential needs and are far less careful (i.e., less calculating) with their finances compared to others (Dorling, 2017:126). Studies show that such behavior, which generates increasing amounts of unnecessary waste, results in a larger ecological footprint and greater pressure on the environment. Ahead of his research, Dorling asked what the environmental benefits of a more equal world might be.

He argues that money, or income, is directly linked to social respect: the greater the income inequality within a society, the stronger the implication that people are valued differently based on how much they earn. This lack of mutual respect, combined with growing socioeconomic differences, “creates a certain degree of selfishness that spills over into a lack of care for the environment or indifference to how our own behavior affects other things as well as other people. This is evident even in water consumption, especially if you imagine replacing the circle of the USA with 50 smaller circles representing its states” (Dorling, 2017:137). Accordingly, Wilkinson and Pickett emphasize that reducing inequality shifts the balance away from what divides us – self-interested consumerism driven by status competition – toward a more socially integrated and affiliative society. In other words, greater equality can help foster a public ethos and a commitment to collective work (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2010:218).

What’s the point of growth if we’re not well?

Building on Wilkinson’s and Pickett’s perspective, the core idea is that democratizing the economy is key to creating a more democratic society. By translating the principles of a “good economy” into practice, communities can strengthen their resilience in times of ongoing crisis and move toward a more sustainable way of life. Models of a good economy promote trust, solidarity, sustainability, and democratic principles, thereby laying the foundations for a high quality of life. Yet, the fundamental question remains: how can these models be successfully implemented, given that our civilization depends on growth and debt, and increasingly frequent crises contribute to rising inequality and social disparities?

Tim Jackson (2009) therefore asked how to separate the achievement of well-being from economic growth, given that well-being has traditionally been linked to growth. However, “once a society reaches a certain level of economic prosperity, variables such as relationships with others, health, safety within the local community, leisure time, and similar factors have a greater influence on further increases in happiness and life satisfaction, while further increases in income have less impact” (Šimleša, citing Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009).

1.6. Šimleša, D. (2007). Kako gazimo planet-Svijet i Hrvatska. U: Lay, V. Razvoj sposoban za budućnost, Zagreb, str 85

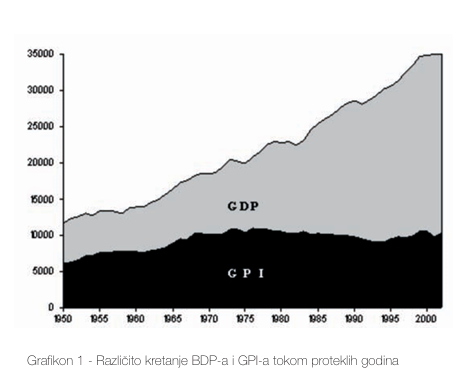

GDP has traditionally been considered the key indicator of a country’s success, but it does not reflect quality of life. The terms “standard of living” and “quality of life” are often confused: the first refers to per capita costs, while the second measures a sense of well-being. GDP does not account for non-monetized aspects such as natural resources or interpersonal relationships. For example, GDP growth can result from environmental degradation or the treatment of disease, which does not necessarily improve living standards. As a result, global institutions like the World Bank often praise countries with high GDP, even though this does not necessarily reflect real progress in quality of life (Šimleša, 2007:79). It is more accurate to track the GPI (Genuine Progress Indicator), which includes all the aspects GDP overlooks, such as the loss of natural resources and social factors like household labor and volunteering. GPI has been shown to produce different results from GDP; in fact, even as GDP grows, quality of life may decline over time (Šimleša, 2007).

Less concrete, more connection: The politics of a greener future

One possible solution, as a variation on democratic socialism, is ecological socialism: a model that “connects the ecological crisis with the social system, constructs a model of green development with a socialist system as the goal, ecological well-being as a core value, and harmony between humans and nature as a fundamental concept” (Xu, 2020:250). Xu further explains that ecological socialism considers the current living conditions and practices shaped by the capitalist system as the cause of the ecological crisis. Key elements of ecological socialism include democratic socialism (democratic economic planning), collective ownership of resources (land, forests, and water) to combat privatization, sustainable production and consumption, as well as social justice and global cooperation (Xu, 2020). This political approach also promotes social justice—ensuring access to basic human needs such as education, healthcare, and housing—alongside global collaboration.

In theory, the solution seems straightforward: replace existing trade and financial agreements that govern globalization with ones that promote truly sustainable and fair collective development. These new agreements would establish clear and binding social and ecological goals, including measurable targets for issues such as multinational tax rates, wealth distribution, carbon emissions, and biodiversity. Rather than making trade a prerequisite, these goals would take priority. However, transitioning from existing agreements to new ones will require patience and the formation of coalitions among like-minded countries. Ideally, agreements on shared development would include a significant democratic transnational dimension, unlike the current vertical logic in which heads of state and their administrations negotiate trade rules among themselves (Piketty, 2022:219).

To make my point…

Public green spaces, such as parks, forests, waterfronts, playgrounds, and urban gardens, have a huge impact on young people’s mental health, social life, and sense of belonging.

In Croatia, for example, many city areas are under pressure from apartment development and commercialization, which means young people are losing places to gather and spend time in nature. And while higher urban densities can enhance infrastructure efficiency and economic vitality, they often create concrete-dominated environments that increase heat exposure, pollution, and social inequalities – posing significant environmental, social, and health challenges that planners must address (Pont et all, 2021).

Ultimately, my point is that the issue of green spaces and youth cannot be viewed in isolation. It is deeply connected to the broader questions of how we organize our societies, distribute resources, and define what constitutes true progress. When the economy is focused only on growth and profit, the result is concrete cities and disconnected people. But if we strive for equality, solidarity, and a “good economy,” we can build cities where everyone has access to clean air, shade, and a quick TikTok break…

Literature:

Dadvand, P., Hariri, S., Abbasi, B., Heshmat, R., Qorbani, M., Motlagh, M., Basagaña, X., & Kelishadi, R. (2019). Use of green spaces, self‐satisfaction and social contacts in adolescents: A population‐based CASPIAN‐V study. Environmental Research, 168, 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.09.033.

Dorling D (2017) The Equality Effect. New Internationalist.

Jackson, T. (2009) Prosperity without Growth – The Transition to a Sustainable Economy, URL:http://www.sdcommission.org.uk/data/files/publications/prosperity_without_growth_report.pdf

Kondo, M., Locke, D., Hazer, M., Mendelson, T., Fix, R., Joshi, A., Latshaw, M., Fry, D., & Mmari, K. (2024). A greening theory of change: How neighborhood greening impacts adolescent health disparities.. American journal of community psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12735.

Mironesco, M. (2020). Service-Learning and Civic Engagement: Environmental Awareness in Hawai‘i. Journal of Political Science Education, 17, 583 – 598. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2020.1777146.

Piketty, T. (2022). A brief history of equality. Harvard University Press.

Pont, M., Haupt, P., Berg, P., Alstäde, V., & Heyman, A. (2021). Systematic review and comparison of densification effects and planning motivations. Buildings and Cities. https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.125.

Šimleša D (2016) Zeleni alati : dobra. Velika Gorica : Zelena mreža aktivističkih grupa

Šimleša, D. (2007). Kako gazimo planet-Svijet i Hrvatska. U: Lay, V. Razvoj sposoban za budućnost, Zagreb, 77-108.

Šimleša, D. (2010). Ekološki otisak: kako je razvoj zgazio održivost. TIM Press.

Wilkinson R, Pickett K (2010) The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone. Penguin.

Xu, J. (2020). Eco-socialist Green Development Model and Its Enlightenment. In 2019 International Conference on Education Science and Economic Development (ICESED 2019) (pp. 441-444). Atlantis Press.

Zhang, Y., Mavoa, S., Zhao, J., Raphael, D., & Smith, M. (2020). The Association between Green Space and Adolescents’ Mental Well-Being: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186640.