Let’s imagine Omar, an ambitious 18-year-old senior in high school living in the northwest region of Tunisia. With a passion for technology, he aspires to become a software engineer. His sister, Fatma, also fervently dreams of pursuing medicine abroad and is currently in her third year of high school, majoring in science.

Omar’s day begins before the break of dawn, preparing himself for a long day that involves commuting an hour away to school. In the evenings, he helps his father, who works as a farmer, tending to their land. This routine leaves little time for leisure or additional studies outside of school hours. Fatma, equally driven, spends her weekends assisting her family with cooking, especially considering her mother’s health condition as a diabetic.

In contrast, Karim’s life takes a different trajectory. He attends a private school and supplements his education with additional tutoring in the evenings. His father’s influential position in a company provides Karim with a direct pathway into the industry he wishes to enter – software engineering. His weekends are dedicated to personal pursuits like the gym and socializing with high school club friends.

Two years down the line, the opportunities and evaluations for Omar, Fatma, and Karim are unlikely to be the same. The disparity in resources, familial responsibilities, access to quality education, and exposure to influential networks will shape their futures in distinct ways. Omar and Fatma, while passionate and hardworking, may face challenges in realizing their aspirations due to limited resources and familial obligations. Meanwhile, Karim’s path seems more streamlined due to his access to better education, familial connections, and fewer domestic responsibilities.

The divergent paths of Omar, Fatma, and Karim underscore a quote by Nelson Mandela: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” However, in regions like North Africa, access to this weapon isn’t uniform, and the ability to wield it effectively is often determined by circumstances beyond an individual’s control.

In North Africa, the starting line for youth pursuing their dreams is not uniform. While some individuals are granted access to quality education, familial support, and opportunities, others like Omar and Fatma contend with familial obligations, limited resources, and a lack of educational infrastructure. These factors, which are often shaped by geographical location, socioeconomic status, and familial responsibilities, establish a fundamentally uneven playing field.

Structural inequalities persist in North Africa, profoundly affecting the opportunities available to its youth. Limited access to quality education due to underfunded schools, insufficient infrastructure, and disparities in resources disproportionately hinder youth from marginalized backgrounds, such as Omar and Fatma. These barriers impede their academic growth and skill development, creating hurdles in pursuing their aspirations.

Moreover, socioeconomic disparities reinforce these inequalities. Families with lower incomes face challenges in providing supplementary educational resources or supporting their children’s career ambitions. This economic disparity restricts access to opportunities that would otherwise foster skill development and exposure to relevant industries.

Furthermore, family background significantly shapes the trajectory of a youth’s opportunities and success. The correlation between a father’s education level and that of their children is a critical factor. Research indicates a strong link between parental education and the educational attainment of their offspring. In cases like Omar and Fatma, where familial responsibilities and limited resources constrain their educational pursuits, the cycle of lower educational achievement might persist across generations.

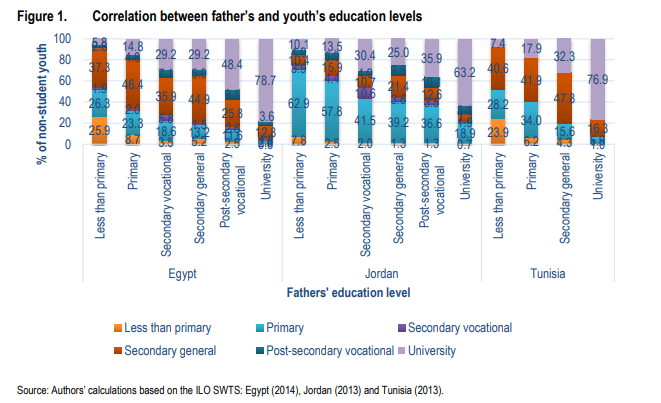

Figure 1 demonstrates the connections between fathers’ educational achievements and those of their children across the three countries. Unsurprisingly, there’s a clear trend showing that children of well-educated fathers tend to attain higher levels of education themselves compared to children whose fathers have lower educational attainment. For instance, in Egypt, a significant 78.7 percent of children whose fathers graduated from university also became university graduates, contrasting starkly with a mere 5.8 percent of children whose fathers had no education. In Tunisia, the proportions are 76.9 percent compared to 7.4 percent, while in Jordan, they stand at 63.2 percent and 10.1 percent respectively.

However, there’s evidence of some movement between generations, particularly among fathers who completed secondary education. Around one-third of the surveyed individuals whose fathers had attained some form of secondary education proceeded to achieve a university education themselves.

Figure 2 illustrates a notable inter-generational association in terms of occupational skills levels, particularly evident within the lower-skilled occupations. Specifically, in Egypt, a substantial 62.9 percent of children whose fathers work in low-skilled occupations also find themselves in similar positions. A similar correlation of 62.0 percent is observed in Tunisia. In contrast, Jordan displays a higher degree of mobility between generations in this aspect. Although 46.9 percent of young individuals tend to work in low-skilled occupations similar to their fathers, nearly 20 percent of them have progressed to high-skilled occupations, and approximately one-third have transitioned to medium-skilled occupations, surpassing their fathers’ occupational levels.

Biased hiring practices further exacerbate these inequities. Discriminatory hiring processes often overlook talent from underprivileged backgrounds, favoring candidates with access to better education or influential networks, as seen in Karim’s case. This perpetuates a cycle where the marginalized youth face hurdles not only in accessing education but also in securing employment opportunities that match their skills and aspirations.

Much like a race where contestants begin from different starting lines and traverse varying terrains, the pursuit of success is nuanced and subjective. Omar, Fatma, and Karim exemplify ambition and dedication, yet their opportunities are inherently shaped by circumstances beyond their control. Consequently, solely measuring success based on achievements without acknowledging the disparities in starting points leads to an incomplete and flawed assessment.

It is crucial for companies and hiring institutions to recognize and actively address the inherent inequalities in opportunity. Acknowledging the unequal access to resources and opportunities is the first step towards instituting measures that level the playing field during recruitment processes. These measures are fundamental in enabling a more equitable evaluation of candidates, ensuring that potential and skills take precedence over background advantages.

Advocating for equal opportunities necessitates systemic changes rather than individual efforts alone. This involves implementing policies that bridge educational disparities, foster fair hiring practices, and account for the diverse starting points of individuals. Striving towards a future where companies and institutions consider and rectify the inequitable access to opportunities is pivotal in cultivating a society that is just, merit-based, and inclusive.

Inequalities in access to opportunities among the youth in North Africa remain an urgent and pressing issue that demands immediate attention. The disparities highlighted in education, occupational pathways, and the influence of family backgrounds underscore the imperative to rectify systemic inequities. It’s time to bridge the gap and offer an equitable platform for every aspiring individual, regardless of their starting point.

To pave the way for a fairer, more inclusive society, actionable steps need to be taken. Firstly, investing in comprehensive educational reforms is pivotal. Initiatives that prioritize quality education for all, irrespective of socioeconomic backgrounds, are essential. Access to educational resources, scholarships, mentorship programs, and vocational training should be made readily available to nurture talents from diverse backgrounds.

Secondly, reforming hiring practices and corporate policies is crucial. Companies must commit to fair recruitment processes that evaluate candidates based on merit, skills, and potential, rather than perpetuating biases linked to social status or family connections. Implementing diversity and inclusion initiatives can foster environments where all talents thrive.

Moreover, societal collaboration is indispensable in this endeavor. Communities, institutions, and policymakers must work in unison to create an ecosystem that empowers every youth to reach their full potential. Advocacy for policy changes that address structural barriers and systemic inequalities is essential for long-term change.

Last but not least, by standing together, advocating for equal opportunities, and driving actionable change, we can create a future where every young individual has an equitable chance to achieve their aspirations and contribute meaningfully to society’s progress. It’s time to shape a narrative where opportunities are not a privilege but a birthright for all.

Finally, despite the challenges faced by under-served youth, the narrative can be rewritten. It’s a call to break the chains of disparity and we will change the storyline, embrace and win the battles our parents never won.